All Pygouvian errors are the same, but some are more equal than others

by Antonio Cabrales Goitia

Today, I am going to tell you something that may surprise you as much as it did me. You don’t have to torture the data much or propose very heterodox theories to take serious action against climate change. The consequences of doing too much are much more benign than those of doing too little. This statement is based on the presidential lecture given by Per Krusell at the annual congress of the European Economic Association, which this year was held virtually for the first time. Per’s lecture, like the other plenaries, is available to everyone here. Don’t miss it because it’s well worth it.

Per has already been mentioned in this blog on multiple occasions. For example, Per’s pioneering article with Anthony Smith taught a generation of macroeconomists to work with heterogeneous agents and today it is rare to see macro models with representative agents. So when someone tells you that the problem with “orthodox” macro is that it assumes representative agents, you know that you have not read anything about modern macro for more than twenty years.

The conference starts with something obvious, climate change is happening, and there is a consensus that it is important to limit it. In contrast, there is less consensus on how to do it. And we economists are very qualified to identify the optimal way to reduce emissions. The recipe was provided by Pigou 100 years ago. We should apply a tax equivalent to the difference between the private marginal cost and the social marginal cost of emissions. Since carbon dioxide is also expanding very rapidly in the atmosphere and affects everyone, the tax must be global.

But if we agree on everything, can we stop investigating now? Per’s answer is clearly negative for three reasons. First, deciding what the optimal tax is is not trivial and requires work from various fields, theoretical and empirical. Second, because perhaps Pigou’s recipe is wrong. To begin with, it assumes the absence of other distortions that should be taken into account. It also assumes that “markets work” and perhaps they do not. And it also assumes that incentives will be sufficient, people are rational and social norms are not important. Third, world leaders do not always follow our recommendations and we want to know what happens under sub-optimal policies. Per’s work will focus on the first and third points. I’ll be sure to bring you some discussion on the other points in other posts.

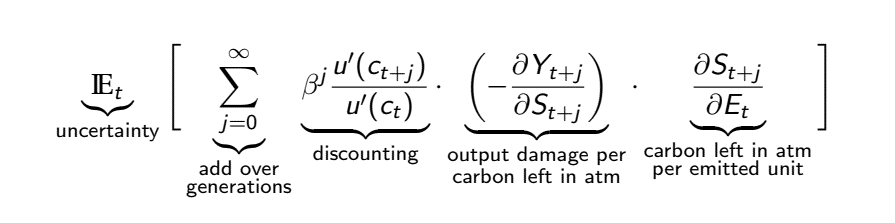

To work on the first point, it is useful to see in a simplified way the formula of the social marginal cost, or “social cost of carbon” (SCC).

The essential elements to realize the complexity of the problem are here. On the one hand, there is uncertainty. In addition, the problem is dynamic and the impact on different generations must be taken into account and potentially discounted (or not). We also have to calculate the damage to the production of the carbon stock in the atmosphere and what the emissions add to that stock.

The next step is to build models such as those advocated by Nordhaus called “integrated assessment models” (or IAM) that use computational general equilibrium methods, calibrated with real data, to calculate the CSC. One important point that emerged from the seminar is that the process of building the preferred model varied from very complicated versions to simpler ones. In the end the simple version was chosen because the complicated ones did not give very different results and obscured the process of understanding the results.

This final model was discrete and infinite in time, with one final good and eight regions in the world (Europe, USA, China, South America, India, Africa, Oceania, and the oil producers – OPEC and Russia). Within each region a single product is produced by a representative agent. The production function uses capital, labor and an energy composite product that has constant, but imperfect, substitution elasticity between different types of energy (oil, other fossil fuels and “green” energy). Total factor productivity incorporates climate change damage, and the marginal cost of energy is constant (zero for oil). The technological change is exogenous and the cycle between carbon and climate is similar to that used by Nordhaus. There is supposed to be perfect competition, and only oil produces income, and it is the only commodity that is traded. Governments have balanced budgets, there are no transfers between countries, and they have a tax on the fossil energy sector that is returned directly by consumers. Clearly there are many limitations to the model: there is no endogenous growth (there could be R&D to accelerate green technologies), nor non-linearity (tipping points that generate abrupt changes, or uncertainty). All these issues are easy to incorporate and do not give giant changes, but make the model much less transparent. On the other hand, as we said at the beginning, it is a completely standard model, without loading the ink or exaggerating in any way the effects of climate change, something that should be kept in mind when we see the conclusions.

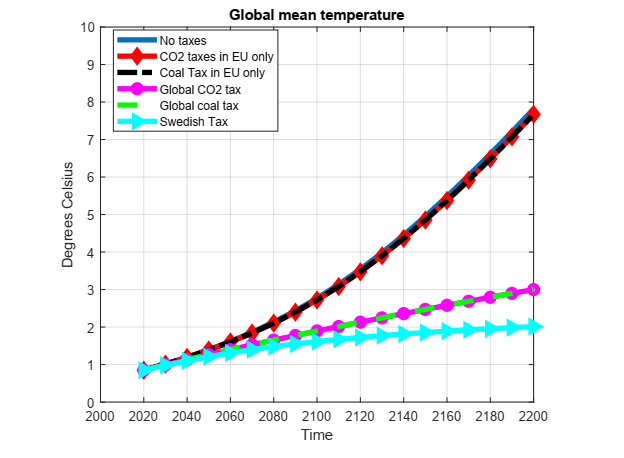

Once calibrated with real data, the model replicates many aspects of today’s real economy very well, despite its simplicity. But what is interesting are the policy implications that we are going to see in a few figures. First in this figure we can see what happens with six policies (in the order of the legend in the figure): 1. no taxes, 2. carbon taxes in the EU only, 3. carbon taxes in the EU only, 4. global carbon taxes, 5. global carbon taxes, 6. global carbon taxes at the level of Sweden There are two aspects to be highlighted. There is not much difference between taxing only coal or all emissions. Taxes have to be global, there is little point in having only the EU do it.

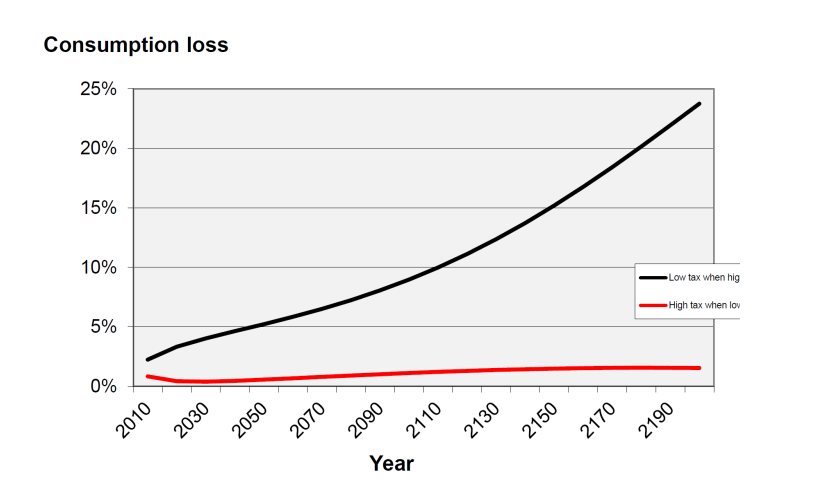

The following chart is for me the most important of the talk.

The black line tells us what happens if we put a tax based on the most optimistic assumptions of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) but the reality is much worse (low tax and severe climate change). The red line is the opposite. A tax based on the IPCC’s pessimistic assumptions is put in place but the reality is better (“high” tax and moderate climate change). The result is extraordinarily striking. An “optimistic” mistake makes us lose a quarter of our income. A “pessimistic” error has practically no effect. The intuition for this result is that starting from a tax almost zero the distortion (the cost) that generates in the economy a “high” tax (which in reality is not so high), is to use a slightly less efficient energy source, which is not a brutal cost and is also easily reversible. On the contrary, emitting too much and letting the atmosphere get too hot because the tax does not sufficiently reduce emissions is catastrophic and irreversible. In this situation it seems clear what we have to do, take the pessimistic scenario and act now.

A couple more observations and I’ll conclude. A non-uniform tax is a bad idea. If we exclude developing countries, especially China, from the tax, the result is disastrous. It is true that most of the current stock has been placed by first world countries. These countries can (should?) be compensated in other ways, but not by not having the Pigouvian tax or we will get almost nothing. The other observation is that pushing green energy is only a bad idea. It is essential to use a Pigouvian tax as well.

So they already know that. Even for a completely orthodox economist, you have to take serious and immediate action on climate change. If someone denies it, he’s not only a denier of physical science, he’s also a bad economist.